A new data model: Making Adaptory 10x faster

(Warning: technical gamedev post)

As alluded to in my previous post, I’ve spent most of the last month or two working on the internal data model of our base building/simulation game Adaptory, to improve the performance of the background simulations. At a high level, it’s looking really good: games now run on average 10x faster (depending on the complexity and size of your game world).

In the rest of this blog post, I’m going to do a bit of a deep-dive into some of the approaches and technical details of these improvements, and share some interim results.

A new read/write model

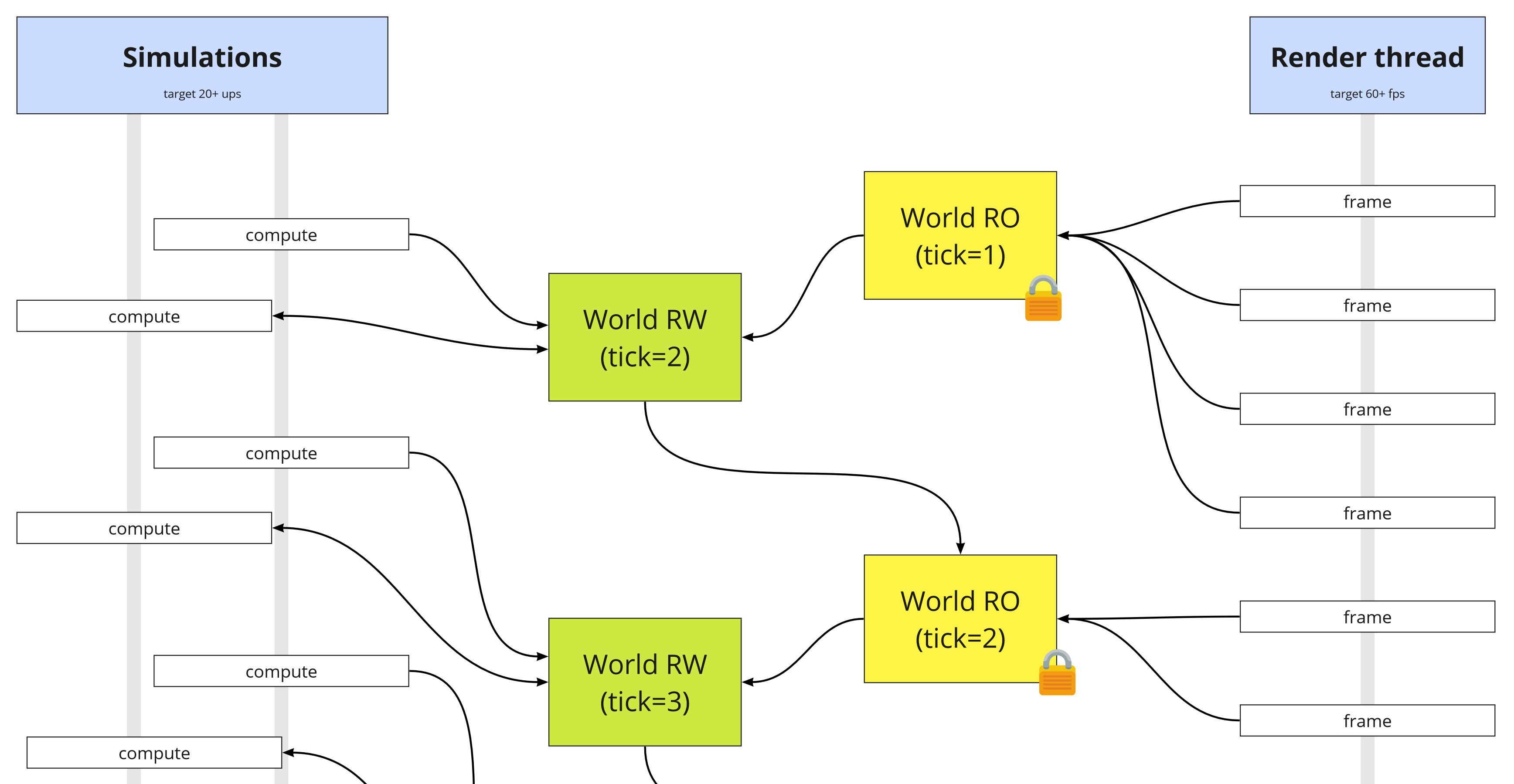

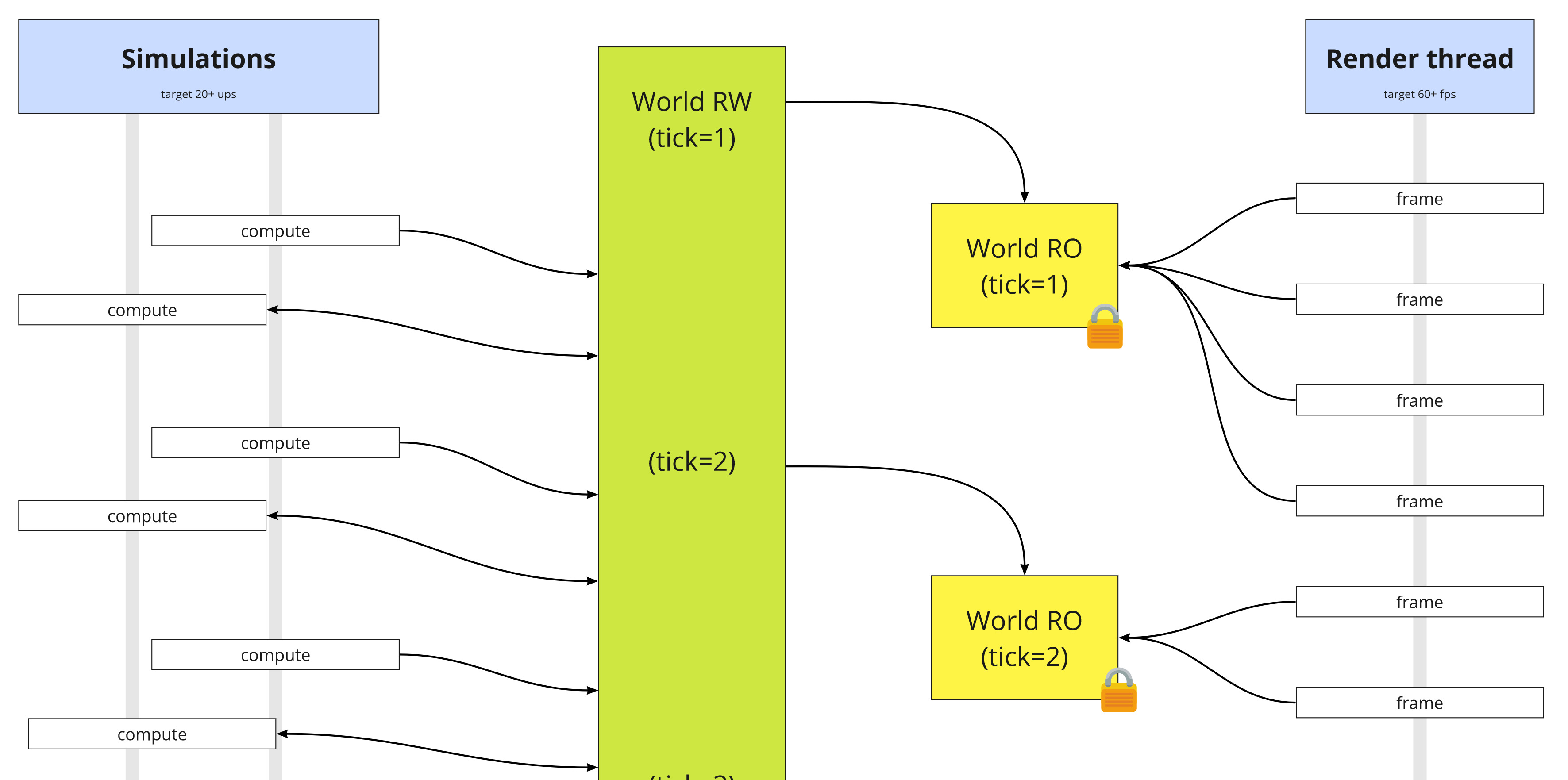

The original architecture split worlds into read-only and read-write versions, so the render threads and long-running simulations would never have to block, and frame-by-frame simulations could have free-for-all access as they saw fit. This guaranteed there was no chance of having concurrent access issues.

However this does mean that memory bandwidth would quickly become a bottleneck. In each frame, you’re having to clone the entire world twice – one from RO to RW, and again from RW to RO.

After creating a lot of tests and infrastructure, I’ve now rebuilt the read/write model to instead have a single writeable version that persists across all frames. “Snapshots” of the world are instead created on-demand for render threads and long-running simulations. I’ve also started work on supporting “partial snapshots” specifically for the render thread.

This new architecture also paves the way for having interleaved simulation threads; not every simulation will require every piece of data, for example. This is much more technically challenging but I’ve designed the API and infstructure to allow this.

Impact: 33% improvement

Sparse maps and lookup caches

In the previous data structure, world objects (such as pawns and buildings) were stored as lists on the world, which meant that in order to find a specific building, the process had to iterate through every object until it found the right one.

In the new data model, world objects can be stored in a sparse map instead. I’ve also added a handful of reverse object caches for faster querying. Not every world object is best stored in sparse map; buildings, for example, are frequently used in tile inaccessibility calculations, and being stored per-cell is still faster.

I’ve also rebuilt the infrastructure and tests used to define worlds and model objects; world objects can now be stored per-cell, sparsely, or as world lists.

(I did investigate the possibility of looking into an RDBMS like sqlite or H2, which provides things like indices and caches for free – but video games are significantly more memory-hungry than most desktop applications, and any serialisation/deserialisation would be too expensive. We’re trying to simulate millions of cells per second!)

Impact: 14% improvement

New derived data/change layer management

Adaptory keeps track of changes to data, so that simulations don’t have to re-calculate data that hadn’t changed since the last tick.

I’ve rewritten these parts to minimise the delay when changing an attribute (of a cell or a world object), and there is now a dedicated change layer manager that manages the different derived layers and when each chunk may be out-of-date.

Impact: 25% improvement

More caches and precalculations

In the errand simulations (which was a major slow part of the previous release), a lot of time was spent finding nearby items and buildings, and calculating tile inaccessibility.

I’ve updated a lot of these simulations to use new caches where appropriate.

Impact: 48% improvement

Plus dozens of other changes, too small to list here

This is just a small list of the changes that will be coming in Alpha 4. There’s been over 350 commits since the previous release, which is why the next update will not have a significant amount of new content – I’ve touched almost every part of the game and I want to make sure I haven’t broken anything!

Some of the major learnings I’ve had over the last few months include:

- there’s no way I could have completed this work without the amazing unit and integration test suites I’d already built

- when building data structures, focus on building an expressive API that starts out pretty generic, but in a way that allows you to quietly replace specific methods with more optimised methods

- the best way to improve performance is to minimise how much data you’re creating, storing, and copying. you’re most likely memory-bound, not CPU-bound

- in order to optimise effectively you need to have reproducible workloads that accurately reflect what your users are seeing

- in Java, don’t expose raw fields – use methods wherever possible, as they make refactoring significantly easier, and your VM will usually inline them anyway

- don’t use Java generics as a way to emulate code generation – your generics definitions will quickly become monstrosities that require repetition every time you use them. try to keep your generics as, er, generic as possible

synchronizedis expensive, can you write your code in a way that doesn’t need it?- it’s better to write your Java methods and classes with reallyLongNamesThatAccuratelyDescribeWhatTheyDo() than shortButVague(). once compiled by the VM, they’re essentially anonymous integers anyway

- I’ve still got a lot to learn about optimising and building good Java software

(Note: Some of these only apply to Java and the HotSpot VM as at JDK 17.)

Future work

Throughout this task I’ve also been focusing on improving the internal APIs so it should be easier to identify slow spots and opportunities to optimise. One of the worst things that a studio can do is to optimise their game too early. I’m hoping that this architecture and model will be strong and resilient enough to take the game through to Early Access/1.0.

I have identified a lot of other opportunities for optimisation, but I need to get back to making a game, and their impact won’t be clear until I’ve built more of the game systems.

(Thanks to the Batman T-Shirt Theory club for their help in putting together the best charts for this post! 😀)